This Art Form Still Inspires Style Today

Writer John Zeaman

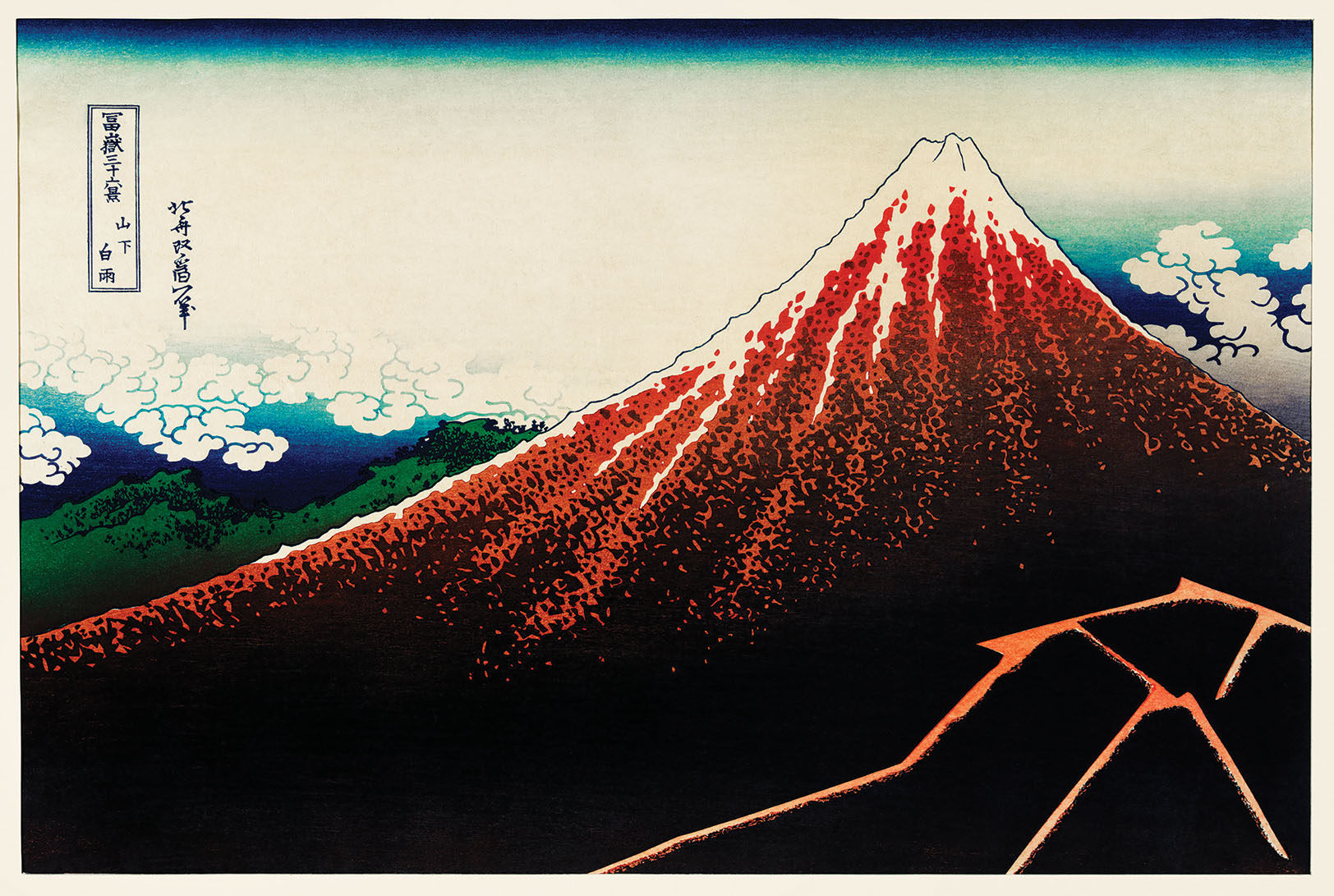

Sanka Hakuu (Shower Below a Summit) by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) is a traditional Japanese ukyio-e style illustration of Mount Fuji. Digitally enhanced by the copyright holder.

Ever since the mid-19th century, when ukiyo-e prints took Paris by storm, Westerners have been enchanted with this Japanese art form. Katsushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave Off Kanagawa is now an icon, even reproduced on T-shirts and coffee mugs. Copies of Utagawa Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo sit on coffee tables everywhere. Ukiyo-e’s pop culture descendants —manga, anime and graphic novels — thrive here and in Japan.

Ukiyo-e means “pictures of the floating world,” a reference to the pleasure districts of Edo (present day Tokyo), which, for a time in the 17th and 18th centuries, was the biggest city in the world. The prints celebrated the delights of its demimonde with images of geisha, kabuki actors, samurai, sumo wrestlers, prostitutes, brothels, teahouses and landscapes.

A modern recut copy of The Great Wave Off Kanagawa from the woodblock print series 36 Views of Mount Fuji by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849). The waves in this iconic work are sometimes mistakenly referred to as tsunami, but are more accurately called okinami (great off-shore waves).

Their style and treatments were embraced by French modernists such as Degas, Manet, Monet, Mary Cassatt, van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec and others. They responded to ukiyo-e’s bold lines and flat areas of color. They liked the feeling of spontaneity that emerged from its abrupt cropping and unexpected viewpoints. So influential was it that the term Japonisme was coined to describe the Western affinity for its effects.

An important difference was that most European artists (with the exception of Toulouse-Lautrec) applied the lessons of Japanese prints to oil painting, a medium in which the artist controls everything. In contrast, ukiyo-e artists were part of a collaboration. Once the artists produced the drawing or design, skilled artisans took over. Carvers made the wood blocks — a separate one for each color. These were passed to the printer who applied ink to the blocks and pressed each block to the handmade paper (washi), one at a time. In the early days, the palettes were limited to a few colors, mainly pinks and greens. As more colors were added, a dozen or more blocks might be required. If the artist’s plan required gradations of color — a sky that varied from light blue to a darker blue, say — the printer had to manually apply the ink in that subtle way. The artist oversaw the process — at least at the outset of the run — and approved it with his stamp.

Ryogoku Hanabi (Fireworks at Ryogoku), created in 1858, is from the woodcut print series Meisho Edo Hyakkei (One Hundred Famous Views of Edo) by Utagawa Hiroshige.

In the 200 years that ukiyo-e prints were produced — from the late 17th to the late 19th centuries — various stars emerged. Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1865) specialized in kabuki scenes and portraits of sumo wrestlers. Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806) made his name with individualized portraits of beautiful women. Utagawa Toyoharu (1735–1814) employed Western-style perspective and pioneered the use of landscape as a subject rather than mere background. The enigmatic Tōshūsai Sharaku (1701-1795) was the first to do portraits of kabuki actors that emphasized the difference between the actor and the portrayed character.

However, no stars shone so bright as those of Hokusai (1760-1849) and Hiroshige (1797-1858).

Like many great pairings in art history, the two were opposites in temperament. Hokusai was the dynamic Dionysian. Hiroshige was the serene and balanced Apollonian.

Hokusai was a legendary draftsman who worked in all media, including paintings, murals and manga (random drawings). He was a caricaturist and a humorous portrayer of everyday people. He also was a tireless self-promoter who changed his name every time he undertook a new phase in his career. At one point, he signed his works Gakyō Rōjin Manji”(The Old Man Mad About Art). His collection titled Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji includes that famous wave (The Great Wave off Kanagawa), in which the distant volcano is framed by the arching, claw-like wave.

Plum Park in Kameido, an 1857 woodcut print by Utagawa Hiroshige (left) compared with Flowering Plum Orchard (after Hiroshige) painted by Vincent van Gogh 30 years later.

Hiroshige came to specialize in landscape. His crowning achievement, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (actually 120 views), was begun in 1856 when he was almost 60. A few months after beginning it, he shaved his head and took formal vows renouncing the world to become a Buddhist priest. In this sense, its “floating-world” was less an allusion to leisure entertainments than to the ultimate transience of all existence. Moonlight, seasonal effects and weather were prominent parts of his compositions, as in the slanting lines of rain in Sudden Shower Over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake. Van Gogh made oil copies of both Sudden Shower and Plum Park in Kameido, a dramatic composition of a bent and expressive trunk sprouting blossoms and long slender branches.

Ōhashi Atake No Yudachi (Sudden Shower Over Shin- Ōhashi Bridge and Atake) is by woodcut print artist Utagawa Hiroshige. It’s from the print series Meisho Edo Hyakkei (One Hundred Famous Views of Edo) and is considered one of the best-known of Hiroshige’s prints.

Hiroshige marked the end of the ukiyo-e tradition, but Japanese woodblock printing continued through the subsequent Meiji period (1868-1912) and continues to this day.

Many of the largest high-quality ukiyo-e collections are in France, Britain and the United States. One of the best belongs to The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which has more than 100,000 prints. Because of their relative fragility and sensitivity to direct light, museums keep most of their collections in library portfolios, accessible only on request.

Owning a genuine print by a ukiyo-e artist is surprisingly easy, unless you are looking for what dealers call “originals.” The word “originals” refers to prints that the artist signed off on. However, the term itself is misleading because there really is no such thing as an original print. All prints are copies.

In Western culture, prints — etchings, say — are generally issued in limited editions. When 100 or 200 imprints are pulled from the metal plate, the plate is destroyed. The limited supply is a way of preserving monetary value by ensuring the market will not be flooded with endless identical prints.

But this system was never used with ukiyo-e prints. Japanese blocks continued to be used for years, even after an artist was dead. Blocks were sold and passed on until they were dull and worn out. When this happened, new blocks were carved. It would be a mistake to assume that these “recarved” blocks were necessarily inferior. Using an authentic print as a template, a talented woodcarver born 100 years after Hiroshige’s death—or one working today—might carve as good a block as the original carver. Ditto for the printer who applied the inks.

Who is to say, then, that a print made this way is not a “real” Hokusai or Hiroshige woodblock print? Dealers have invented a flock of terms— some derogatory, some euphemistic, depending on what they are trying to sell—that are supposed to reflect degrees of authenticity. In addition to “originals,” there are “early prints,” “reprints,” “pirated editions,” “fakes,” “antiques,” “vintage” and “reproductions.”

Kobikicho Arayashiki Koiseya Ochie by Utamaro Kitagawa (1753-1806), a traditional Japanese Ukyio-e style illustration of a Japanese woman portrait reading a book. Digitally enhanced from our own original edition.

In my own case, I am happy to own several ukiyo-e prints that are not “originals,” but which look just as good to me. My standards are not those of a serious connoisseur or collector. What matters to me is that the prints match those that can be found in reference books and are from real woodblocks and printed on washi paper. Photo reproductions made with high-quality inkjet printers may look fine at a glance, but real block prints have a tangible handmade quality. One sure way to tell is that the print will reveal traces of ink that have seeped through the back of the thin paper.

A quality modern reprint can be had for as little as $100. Antique prints are proportionately higher, depending on age and condition. With higher priced prints, it’s best to consult reference books or to track down an authentic version in a museum for comparison.

Katsukawa Shunko I (1743-1812) is known for woodcut prints of actors, including Bust Portrait of the Actor Ichikawa Monnosuke II in the Role of Soga No Goro.

Nothing is foolproof. Sometimes the artists themselves made changes to a block, resulting in two somewhat different versions of the same subject, though both “original.” Hokusai once wrote directly to a block cutter, asking that alterations be made to the eyes and noses of the figures in a series of prints because they had not been reproduced in his style. His letter included illustrations of these features in correct and incorrect versions to show what he meant. The publisher ultimately agreed to make these alterations, even with hundreds of copies of the book already printed. A piece of block was cut away and a new piece carefully inserted.

Who knows which would be considered more valuable today? To a collector, the ones with the wrong eyes and noses might be valued as more rare and unusual, in the same way that stamp collectors value misprints above all. For the rest of us, it’s usually enough to have a beautiful print designed by a master artist and produced according to age-old methods.

Columnist John Zeaman is a freelance art critic who writes regularly for The Record and Star Ledger newspapers. His reviews of exhibits in New Jersey have garnered awards from the New Jersey Press Association, the Society of Professional Journalists (New Jersey chapter) and the Manhattan-based Society of Silurians, the nation’s oldest press club. He is the author of Dog Walks Man (Lyons Press, September 2010) about art, landscape and dog walking.